I love a man who’s passionate about principles. From the perspective of a romance novelist, they make the best heroes and it’s Victorian philanthropist Lord Anthony Ashley-Cooper, 7th Earl of Shaftsbury who’s the inspiration for the passionate reformist MP hero of my latest Choc Lit release ‘The Maid of Milan’.

Lord Anthony Ashley-Cooper.

Source: en.wikipedia.org

Not only was Lord Ashley passionate about revealing the misery, depravity and exploitation of thousands of men, women and children who toiled beneath the earth, he was savvy when it came to PR.

By focusing on girls and women wearing trousers and working bare breasted in the presence of boys and men in the coal mines thus making them “unsuitable for marriage and unfit to be mothers”, he was appealing to the sensibilities of the times: A woman’s place was definitely in the home.

Source: bbc.co.uk

The initial enquiry that led to what would be known as the Mines & Collieries Act of 1842, was ordered by Queen Victoria following a freak accident in 1838 at Huskar Colliery in Silkstone, near Barnsley, in which 26 children died: 11 girls aged from 8 to 16 and 15 boys aged between 9 and 12 years.

This led to Lord Ashley’s Commission to enquire into the employment of children.

The conditions uncovered in the coal mines were appalling. The majority of workers underground were less than thirteen years old, many having started their working lives at the age of four or five; first as a ‘trapper’ who opened and closed the doors for the ‘whirley’ or coal-carriage. Due to the complicated ventilation of a mine, and the potential for explosion if the doors were left open, this was an important job and a child not doing its job was severely punished. Therefore, too frightened to go to sleep, the ‘trapper’ worked for up to fourteen hours a day, amidst rats and other vermin, with only Sundays off. Sometimes these small children were required to work “double shifts”.

Source: polarbearstale.blogspot.com

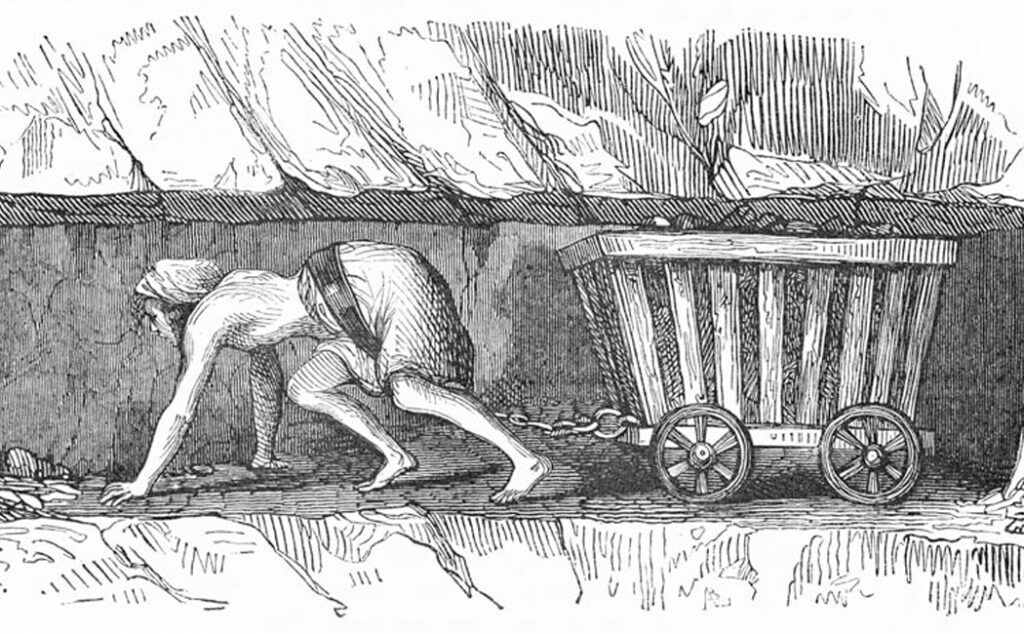

As they grew older, the trappers moved onto other work. Girls carried the same weights as boys, loading and pushing wagons filled with coal along the passages, as did women, even to their final hour of pregnancy. Topless and working in the presence of completely naked men, these women did the work of beasts of burden. The advantage to their employer was that, being small, they could crawl through the tunnels which were often only 18 to 24 inches high, and this they did for twelve to fourteen hours a day, hauling the coal wagons to which they were attached with chains.

Nice, for the employer, was that they didn’t have to pay women and children as much as men.

These were just some of the abuses included in the Report of the Commission and although it aroused the indignation of the nation and the sympathy and support of the Prince Consort, it encountered great opposition in the parliament. (Vested interests, of course.

Finally, though, on 10th of August 1842, The Mines Act, became law, prohibiting female labour as well as the employment of boys under ten years old in coal mines. (Lord Ashley had wanted the age to be thirteen.) It demanded more inspections underground however it did not regulate the working hours of the miners.

Queen Victoria ordered an inquiry that led to the Mines & Collieries Act of 1842, following an accident in 1838 at Huskar Colliery in Silkstone.

Source: en.wikipedia.org

Nevertheless, from this moment women were prohibited from working in the mines. The male coal miners were pleased, too, as the lower wages paid to women had eroded their earning power.

And so women were relegated to the domain they belonged: the sanctity of the home where they reigned as the ‘angel in the house’, a very Victorian concept and a source of conflict in my novel. My once ‘wild child’ heroine is now a model of decorum but now that her reformist MP is making his mark on the world she is terrified of having her wicked past exposed.

The horrors endured by the women in the coal mines is a world away from my heroine’s experience. Nevertheless, her worries, as an upper middle class young woman elevated to the gentry, reveal an exploitation far more subtle and it’s the psychological pressure on these ‘hothouse-nurtured’ women that I explore in my novel.