Life in Ancient Egypt was a bit different for women compared to other ancient societies, where women had very few rights. Though the traditional roles for men and women were different, it wasn’t a big deal if those social roles sometimes overlapped or were even transgressed.

Women in Ancient Egypt were part of the community, and not only seen as wives or mothers.

Women in Ancient Egypt were part of the community, and not only seen as wives or mothers.

Source: mitchellteachers.org

Egyptian women kept ownership of their own belongings when they married, were able to sign contracts and serve on juries, and could even own their own businesses. Women could be doctors, priests, and even, on occasion, Pharaohs.

Traditionally, the Pharaoh was considered an earthly aspect of the god Horus, the son of Ra. A Pharaoh could only ascend to the throne when he married his eldest sister, through whom his divine bloodline was kept pure and passed on to his heirs.

But there are occasional examples in Egyptian history of a woman coming to power, either as regent for an underage heir, or as the only remaining heir of the bloodline. Some of these women claimed a divine right to rule, and took on the male trappings of kingly power, like male titles and dress. Combine this with the fact that rulers often changed their names upon ascension and used multiple royal titles, it makes it hard to know for sure if some pharaohs were male or female. These four women are a few that Egyptologists have agreed ruled Egypt as Pharaoh, though there are many more possible candidates throughout Egypt’s history.

Sobekneferu

A headless statue of Sobekneferu in the Louvre

A headless statue of Sobekneferu in the Louvre

Source: Wikipedia

Sobekneferu is the first woman who ruled Egypt in her own right…that we know of for certain. Her name means “the beauty of Sobek,” a complex deity whose purview included crocodiles, fertility, military might, and the power of Pharaohs.

Sobekneferu’s father Pharaoh Amenemhat III had a son Amenemhat IV who has heir to the throne. But Amenemhat IV died soon after he succeeded his father, leaving no heirs. Sobekneferu, the sole surviving heir, then became Pharaoh in 1806 BCE. Sobekneferu used a combination of feminine and masculine titles as Pharaoh, probably to consolidate her power and mollify detractors of a female Pharaoh.

Official records of Sobekneferu’s four-year rule are scarce, but she did leave behind a surprising amount of monuments, artefacts, and statues for such a short reign. One of the statues thought to depict her is unique in that the figure wears a combination of male and female dress, echoing her use of titles.

After her short reign, Sobekneferu also died without heirs, ending the 12th Dynasty of Egypt and the prosperous Golden Age of the Middle Kingdom. The particulars of her demise are as scarce as details of her reign.

Hatshepsut

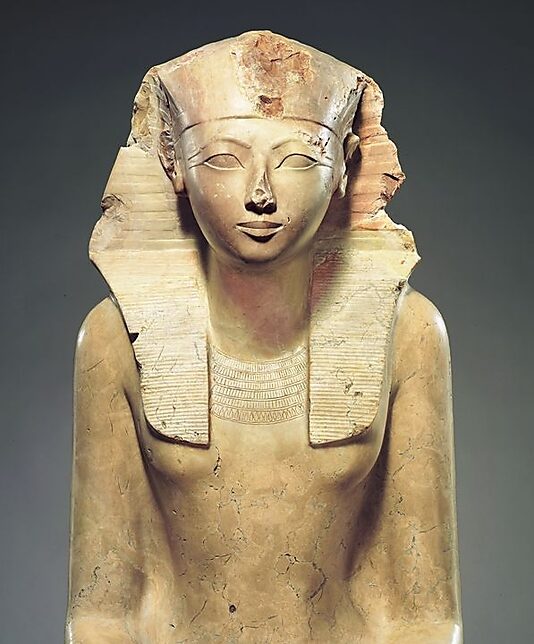

Seated Statue of Hatshepsut

Source: MetMuseum

Hatshepsut was one of the most successful pharaohs in the history of Ancient Egypt, male or female. The beginning of her 15th Century BC reign was fraught with war, but she was able to battle her way to victory and usher in an era of peace, growing Egypt’s wealth through re-establishing old trade routes.

The only child of King Thutmose I and his first wife, Hatshepsut was destined to be queen from birth. When she was 12 years old, her father died, and she married her half-brother Thutmose II, who was the son of a lesser wife of the king. Thutmose II reigned as pharaoh, while Hatshepsut, whose name means “Foremost of Noble Ladies,” was queen at his side. Gradually, Hatshepsut increased in influence, winning over powerful supporters such as Senenmut, an architect and advisor also rumoured to be her lover.

When her husband died after a 15-year reign, Hatshepsut was still in her 20s. Hatshepsut became regent for their only son Thutmose III who still too young to rule. Over the next few years she began to take on more of the trappings of the role of pharaoh, asserting her authority by assuming the titles and ceremonial clothing of a Pharaoh, even donning a false beard. Eventually she even dropped the feminine -t ending on her name, becoming known as Hatshepsu. She claimed the divine right to rule through her bloodline, calling herself the “female Horus.” Seven years into her tenure as regent, she had herself crowned Pharaoh in her own right.

In the beginning of her reign, she led successful military campaigns against Nubia, Syria, and other foreign lands, before turning her attentions to the more peaceful pursuits of trading and building. Years before her rule, Egypt had been a trade partner with the distant Land of Punt, but warfare had interrupted the relationship. Hatshepsut re-established the old trade networks, organizing a huge expedition in the ninth year of her reign. Scenes of the expedition, which brought back treasures like gold, ivory, myrrh, were immortalized on the walls of her mortuary temple.

Hatshepsut started using the wealth she gained through trade to immortalize her 20-year reign by building monuments. She built a temple dedicated to Amon called Djeser-djeseru (“holiest of holy places”), built in an unusual terraced style on steep cliffs, which served as her mortuary temple. One of several obelisks she built still stands today at the Temple of Amon at Karnak. Another obelisk, which remained unfinished at the end of her reign, would have been the heaviest obelisk ever cut in Kemet, weighing nearly 1100 tons and standing 42 meters tall.

When Hatshepsut died in 1458 BCE, her son Thutmose III, general of Hatshepsut’s army, was finally able to take the throne. He returned Egypt to a more military focus, sending campaigns to expand his rule to Syria and Palestine. A decade or two after his ascension to the throne, he began systematically destroying any mention or image of his mother Pharaoh Hatshepsut in an attempt to eradicate her memory, defacing her monuments and building walls around her obelisks. Though the destruction was probably an attempt to consolidate his rule and ensure no challenge to his son’s succession, some historians speculate it was out of spite for his mother’s long and successful reign.