In The White Queen TV series, Margaret Beaufort is an overly religious zealot who hates her mother, loves Jasper Tudor, and was obsessed with her son. The real Margaret Beaufort was close to her mother, happiest with Stafford, and there’s no evidence she loved Jasper Tudor. Nonetheless, Margaret was a remarkable woman – indomitable, shrewd, and strategic. Did early suffering make the young Margaret believe she had to be destined for greatness? You be the judge.

Source: en.wikipedia.org

Margaret Beaufort must have known early on that she was a star: she was a duke’s daughter, the greatest heiress in England, and a possible heir to Henry VI’s throne. Her first possible marriage led to the downfall of England’s most powerful man. Her second marriage to Edmund Tudor produced a future king of England. And, all this happened before she finished puberty. If Margaret felt special, however, she probably felt her uniqueness came at a cost.

Just before Margaret’s first birthday, her father, a disgraced duke, may have committed suicide – deeply dishonorable in the Middle Ages. After John Beaufort’s death, Margaret had no protector and soon became the ward of the king’s own ‘puppet master’ William de la Pole (Earl of Suffolk).

Source: en.wikipedia.org

Suffolk quickly betrothed and possibly married one-year old Margaret to his two-year old son – an act that proved to be a fatal mistake. When Margaret was six, people came to see her as an heir to the childless Henry VI. Suffolk’s detractors charged he intended to use the Beaufort marriage to crown his son, so Henry VI banished Suffolk for five years. Sailing to Calais, Suffolk’s enemies captured his ship, staged a mock trial, and beheaded him on the shore.

With her guardian now dead, Margaret’s life sharply altered course. Queen Margaret of Anjou summoned Margaret and her mother to court. Henry VI dissolved Margaret’s marriage and gave her wardship to his half-brothers Edmund and Jasper Tudor. Henry probably decided to marry Margaret to Edmund to bolster his claim to the throne.

Edmund married Margaret shortly after she turned twelve, the age of consent. Spurred on by greed, he hastily consummated the marriage. If he could impregnate Margaret, he would share in her estates for life. By mid-1456, Edmund succeeded: Margaret was thirteen years old and pregnant.

Meanwhile, the Wars of the Roses had begun and Edmund left Margaret to fight, where Yorkists captured him and he succumbed to plague that November. Being a potential claimant during a fight over who gets to be king endangered the heavily pregnant Margaret. Immediately, she travelled across plague-infested Wales to seek Jasper’s protection.

In a wind-torn tower at Pembroke Castle, the physically immature Margaret nearly died birthing a sickly Henry Tudor. But the experience left scars. There is evidence from later in her life that sex repulsed her and she never had children again – either due to the damage from the delivery or avoidance.

Source: en.wikipedia.org

With Edmund dead, the teenage mother’s lands and son were vulnerable. While Margaret was likely grateful to Jasper for the safe refuge, there is no record of romance. Two months after giving birth, Margaret rode to the mighty Duke of Buckingham and negotiated a marriage between herself and his second son, Henry Stafford.

Margaret’s marriage to the mild-mannered Stafford may have been her happiest period. Both enjoyed hunting and collaborated on household administration. Moreover, they lived near her mother, so she visited often. Margaret, her mother, and half-siblings appear to have been close. Margaret’s administrative style and piety mirrored that of her mother. Margaret stitched a family tree for her half-siblings. Throughout her life, she took an interest in their welfare.

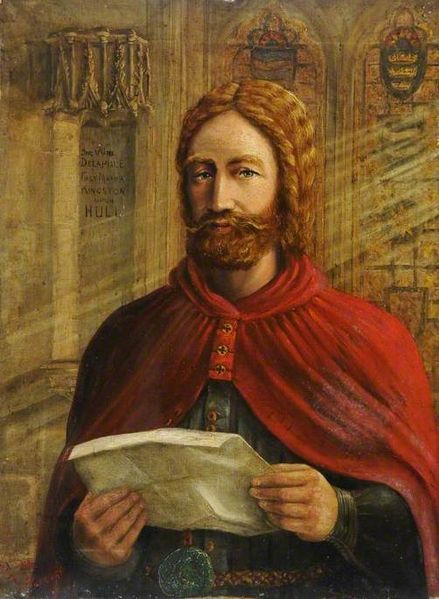

Margaret’s husband, Henry Stafford.

Source: nicolequinnnarrates.blogspot.com

Jasper may have looked after Henry until he was about five. After Jasper lost at Towton, Edward IV sold Herbert Henry’s wardship. Margaret probably didn’t seethe at Herbert’s custodianship. While she would have undoubtedly preferred a higher-born Lancastrian, her interests and Herbert’s aligned. Herbert wanted Henry’s titles restored since Herbert intended to wed him to his daughter.

While touring the West Country in 1467, Margaret “found time,” as historian Desmond Seward puts it, to visit Henry for a week at Raglan Castle. This was her first visit in several years, and Seward notes it wasn’t as though Henry was a prisoner. This doesn’t mean Margaret was a bad mother. Noble sons commonly boarded in other noble households for networking purposes.

Margaret’s ironwill and strategic mind likely resulted from her harsh early days in an age when political missteps led to death and winner took all. Later in life, Margaret signed her name Margaret R likely for “regina” and scarcely yielded precedence to the queen. Her true motives to secure her son’s place seem less saintly in this light. Perhaps her early days as Henry VI’s heir left a craving for queenship. Maybe she overcompensated for the shame of her father’s suicide.