When you think of women in the Middle Ages/early Renaissance, you probably imagine fair maidens, wives, mothers, nuns and possibly widows. Some people know about a special group of women religious called anchorites, who were literally walled off from the world to pray and devote themselves to God. But very few people have ever heard of another option: becoming a Vowess.

What Being a Vowess Meant

Vowesses were women who swore to live the rest of their lives without men in order to become closer to God. They could live in their family home or with a religious community, where they would be supported by charity. Before Henry VIII’s break with the Catholic Church, the Church actually encouraged widows not to remarry and offered them legal protection from relatives, the king or whomever else may harass them if they became Vowesses.

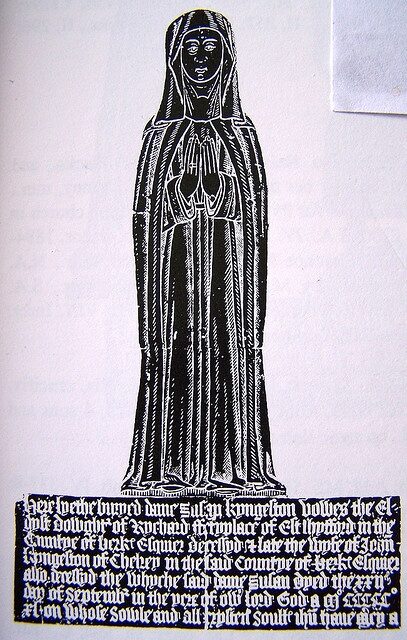

Because of this, Vowesses were most often widows, but could be single women or married women. A married woman would have to have the permission of her husband because they would have to be sexually celibate. If he died first, she would sometimes become a nun or remain a Vowess. Most Vowesses for whom historians have record were wealthy women (wives of knights, aristocrats and urban women), but that could be because their ceremonies were recorded, whereas poorer women were likely to take private vows.

Becoming a Vowess moved her out from under the authority of the king (because she was no longer vowed to her husband, who was under the king’s realm) and into the authority of the Church, usually represented by the local archbishop. This gave Vowesses a usual degree of safety and independence. They could not be forced to remarry by male relatives eager to increase the family standing, by men who coveted their fortunes, or even by their rulers, who often used them (if they were nobles) to satisfy their own political ends. They could do what they wanted with their money, and often gave it to charity. And because they were still considered lay women, they could go where they pleased, as opposed to nuns being cloistered.

Vowesses were often wealthy because widows were entitled to a dower, a share in their late husband’s estate and goods. Sometimes male relatives, even sons, could fight this, and the widow would have to sue for it. Taking vows gave her a stable legal status where she could get what was owed to her.

Taking the vow

Vowesses only took one vow: that of chastity, though they could chose to add others if they wished. Unlike nuns, they did not follow a specific rule of life, and they continued using their married name, not a new one in religion.

If they later changed their minds and wanted to remarry, Papal dispensation was needed. If it was not sought or received, the couple was given a penance, a far more mild punishment than the breaking of solemn vows that occurred if a priest or nun married.

The ceremony was simple and closely related to the one undertaken by women becoming nuns. It was officially to be performed before a bishop, but 79% were delegated to a local priest. The order went something like this:

- After the gospel was read, the future Vowess approached the bishop with two male relations as witnesses. She wore an ordinary dress and carried the dark widow’s clothing (long gown, mantle, and wimple) that would be her habit over one arm.

- She knelt at the bishop’s feet, read she vow aloud, signed it and placed it in his care.

- The bishop blessed her ring and new clothing, before placing the ring on her finger. She prostrated herself as he said the concluding prayers.

- Mass continued as usual.

- At the end she received the bishop’s blessing and kissed his ring.

Anna the prophetess, St. Anne mother of Mary, and St. Elizabeth of Hungry were considered patron saints of Vowesses.

Mary Erler cites a list of 251 vowed women known to exist from 1251-1537, though the vocation is believed to date back to apostolic times. The letters to Timothy, especially 5:3-16, are often cited as referring to special groups of widows and interestingly, Vowesses appear in AEthelred’s 1008 code of law.