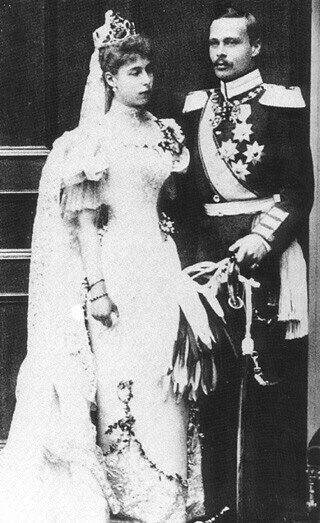

It’s difficult, looking at this photograph of Princess Ducky, to believe it was taken when she was a teenager. But of course teenagers hadn’t been invented in the 1890s and the prescribed destiny of a granddaughter of Queen Victoria was enough to make anyone look glum. They were expected to marry, preferably a suitable cousin chosen for them by their grandmamma, and they should marry young, before they had time to get too many ideas of their own. Unfortunately for Ducky this grandmotherly matchmaking came too late. By the age of fifteen she’d already fallen in love with an unsuitable cousin.

The moment I saw Ducky’s face I sensed a story. I was also, somewhat whimsically, drawn to her by the fact we shared the same birthday. The story turned out to be bigger than I could have imagined, though it started quietly enough. She was born Princess Victoria Melita but for reasons no-one could remember was always known as Ducky.

Her father, the Duke of Edinburgh, was a serving naval officer and later, when one of those occasional royal vacancies occurred, he got booted upstairs to be the Grand Duke of Coburg. Ducky’s mother was the daughter of Tsar Alexander II. An illustrious pedigree but a modest, closeted life. In those days princesses didn’t go to night clubs.

The great love of Ducky’s life was her Russian cousin Grand Duke Cyril Romanov, but Queen Victoria wasn’t keen on Russians, even if they were relatives. She thought them too foreign. So Ducky was bundled into marriage with another cousin, the ravishingly good-looking but reluctant Ernest of Hesse. Married life must have come as a shock to many Victorian girls but in Ducky’s case she had to deal with something that polite people never discussed and ladies were not supposed to know about: Ernie’s preference for boys.

Today divorce, even in the Royal Family, is unremarkable. In the 1890s it was unthinkable. But Ducky did think of it and pressed for it, encouraged by the knowledge that Cousin Cyril wanted her as much as she wanted him. They had a long wait, sometimes hindered by Cyril’s cautiousness – he wasn’t a man given to impetuous gestures – but after the death of Queen Victoria they at last felt free to marry. It was a marriage begun in exile, but eventually it drew Ducky into the glittering world of Imperial Russia, then the Revolution of 1917, and finally into exile again.

Ducky left no memoir, but I needed to give her a voice. It’s a responsibility every novelist must take when they write about the lives of real people. My procedure is to read a biography, if one exists (in Ducky’s case I read Michael John Sullivan’s A Fatal Passion) and then I wait, with my novelist’s ear cocked. I found Ducky came to me without much bidding. Her early life was sheltered and genteel, but again and again she proved to be courageous and decisive. She endured the worst thing that can befall any woman – the death of a child – and survived other losses too, of home and friends and family.

In later photographs Ducky looks tired. She was only fifty nine when she died though she looked older. Her life spanned extraordinary lost worlds – Victorian England, Imperial Russia – but it was bracketed by simple domesticity: childhood in a Navy house in Devonport, and then the final years of her life as a housewife in Brittany. She was, ultimately, the Grand Duchess of Nowhere.

THE GRAND DUCHESS OF NOWHERE by Laurie Graham is published by Quercus on 2 October, hardback £19.99.