The Lunatics are taking over the asylum! There have been some weird cures for mental illness over the years, some have worked, but the majority have been downright bonkers. Here is our round up of the 10 weirdest cures for mental illness through history…

Detail from The Extraction of the Stone of Madness, a painting by Hieronymus Bosch depicting trepanation (c.1488-1516) (Source: Wikipedia)

Detail from The Extraction of the Stone of Madness, a painting by Hieronymus Bosch depicting trepanation (c.1488-1516) (Source: Wikipedia)

This is one of the earliest known forms of psychiatric treatment. A hole would be carefully cut or drilled into the skull to the allow demons supposedly possessing a mentally ill person to escape. From the Neolithic era to the twentieth century, cultures all over the world have used this technique, as shown by the archaeological evidence of skulls with little round holes in them. It would have been painful and dangerous, but might sometimes have worked – by relieving pressure on the skull in the case of tumours or the build-up of fluid.

Painting by Francisco Goya of Saint Francis Borgia performing an exorcism (Source: Wikipedia)

During the medieval period, mental illness was often believed to be caused by demonic possession or witchcraft. The first option for removing a demon was to coax it out of the possessed person. If this was unsuccessful, the next option would be to insult the demon out. If insults failed, the possessed individual was made so uncomfortable that the demon would not want to remain. This might involve mild interventions such as shaving the hair into the shape of a cross, or more radical procedures like dunking in hot water, sulphur fumes, beating or torture. Sometimes the patients died, but at least the demon was gone…

Saint Dymphna: image from holy card (Source: Wikipedia)

St Dymphna was born in 7th century Ireland. When her father tried to incestuously marry her, she fled to Gheel in Belgium, and devoted herself to caring for the sick. When her tomb was uncovered years later, it was said to have cured people of epilepsy and mental illness. Dymphna’s renown spread, and thousands of pilgrims poured into Gheel, seeking help for mental illness. The townspeople took them into their own homes, where they were called ‘boarders’ and treated as members of the family. This phenomenon of Christian community care reached its peak in the 1930s, when over 4,000 boarders lived in Gheel. Dymphna is still the patron saint of the mentally ill, psychologists, psychiatrists, and neurologists.

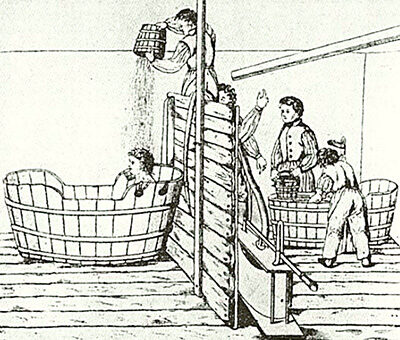

Water therapy in 18th Century Britan (Source: englishhistoryauthors)

In the eighteenth century patients in Bedlam were repeatedly dunked in freezing water in a ducking-stool. This did nothing to improve their mental condition, but like many eighteenth century medical treatments – diets, vomits, laxatives and blood-letting – it frightened and weakened the patient into docility, making things easier for their carers, and giving the impression that they had improved. Water treatments continued into the twentieth century, with increasing zealotry. Patients were strapped down and blasted with high-pressure jets, mummified in towels soaked in icy water, or strapped in baths for days. Personally, I’d rather go to a nice spa.

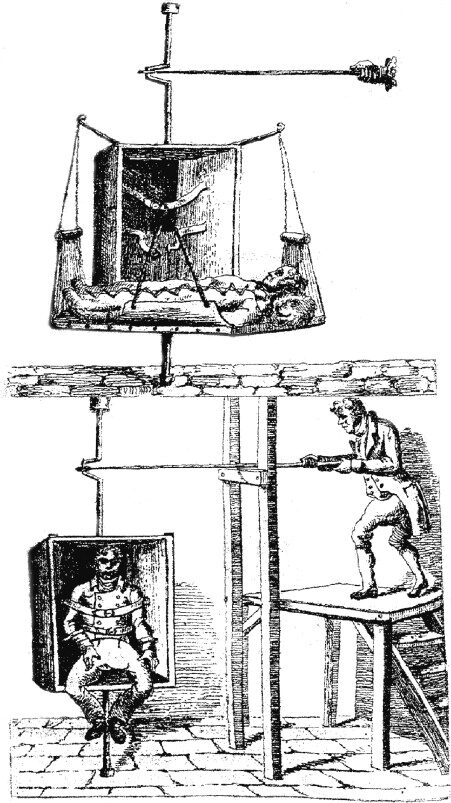

Rotating device (Source: National Library of Medicine)

Charles Darwin’s grandfather Erasmus was a wacky character. He was at the forefront of the scientific enlightenment, wrote an epic poem about the sex-life of plants, and came up with the absurd ‘rotational therapy’. He thought that spinning around really fast could bring on a restful sleep that would cure disease. American doctor Benjamin Rush adopted the treatment for mental illness, suspending a chair to the ceiling and spinning it around on ropes. Instead of a healing slumber, the patients were dizzy and sick. They might have been shocked into temporary submission, but they never actually felt any better.

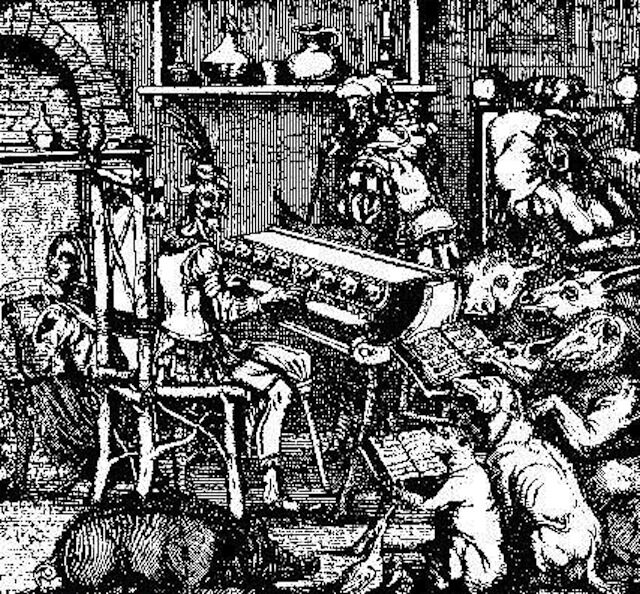

The Katzenklavier: A 17th Century piano that slashed kittens with sharpened nails (Source: Vice)

In the late eighteenth century the German physician Johann Christian Reil came up with a bizarre and terrifying contraption called the Katzenklavier, or ‘cat piano’. This involved pinning down a line of cats and bashing their tails with a hammer or metal spike, forcing them to yowl with pain. Reil thought that if patients who had lost the ability to focus could only listen to this instrument, it would inevitably capture their attention and they would be cured. It was certainly attention –grabbing, but possibly more likely to drive you crazy than cure mental illness.

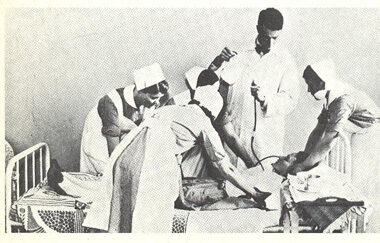

A photo from 1934 showing a malarial transfusion from a patient (seated in the back) to a neurosyphilitic patient (seated most anteriorly). Dr. Julius Wagner-Jauregg is seen standing in the suit on the right (Source: discovermagazine.com)

Late-stage tertiary syphilis was one of the leading causes of psychiatric problems in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. It was a horrible and fatal condition with a range of symptoms including paralysis and delusions. In 1917 Austrian psychiatrist Julius Wagner-Jauregg hit upon a strange cure, after noticing that a psychotic patient got better after suffering a streptococcal infection. He started injecting psychiatric patients with malarial blood to induce a similar fever, controlling it with quinine. Remarkably, the treatment was fairly effective, dramatically improving the condition of 50% of patients with late-stage syphilis. Wagner-Juaregg won the Nobel Prize for medicine in 1927 for his discovery. This dangerous treatment became redundant when antibiotics became widely available after the Second World War.

Insulin shock therapy administered in Lapinlahti Hospital, Helsinki in the 1950s (Source: Wikipedia)

In the 1920s many doctors wrongly thought that epilepsy and schizophrenia could not exist in the same patient. They therefore believed that convulsions and comas could somehow protect against mental illness. In 1927 Austrian-American psychiatrist Manfred Sakel put this theory to the test with an exceptionally awful treatment. He injected schizophrenic patients with large amounts of insulin to induce a coma, bringing them round again with glucose. He repeated this every day for months. Side effects inevitably included obesity, and could include brain-damage and death. The treatment was useless, but it acted as a placebo for doctors, making them feel like they were actually doing something useful. For that reason alone it was incredibly popular throughout the 1940s and 50s.

Illustration of Timothy Leary for TIME by John Ritter (Source: TIME).

In the 1950s Sandoz Laboratories started manufacturing LSD and soon psychiatric patients all around America were being experimented on – about 40,000 patients had taken part in LSD trials by the 1960s. In theory LSD could ‘open the doors of perception’, thus enhancing psychoanalysis. The infamous Timothy Leary, who exhorted people to ‘turn on, tune in, drop out’ even experimented with psychedelics during ‘the Concord prison experiment’, and found that it reduced criminal tendencies. Despite the large numbers of trials, no-one ever really proved that psychedelics could cure mental illness, and the jury remains out.

L. Ron Hubbard (Source: scientology-memphis)

L. Ron Hubbard introduced Dianetics to the public in 1950, with an article in Astounding Science Fiction magazine. He proposed that the ‘reactive’ mind stored up traumas, but that people could become ‘clear’ – free of the reactive mind altogether – with a form of talking therapy called ‘auditing’. Hubbard claims that Dianetics could increase intelligence, alleviate illnesses, ‘cure’ homosexuality and even prevent death. Medics branded it a pseudo-science. Hubbard retaliated by claiming that a secret group of conspiratorial psychiatrists were running the world. Hubbard soon returned to his sci-fi roots, weaving aliens together with eastern philosophy and western therapy to create scientology, and making bucket-loads of cash by preying on vulnerable people with this secretive cult.