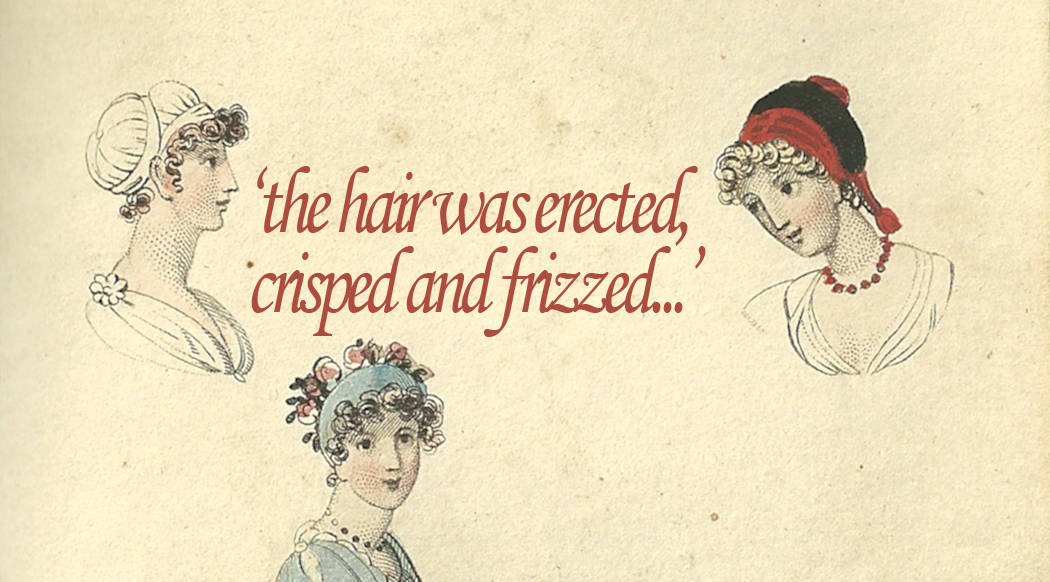

Jane Austen, author of Pride and Prejudice (1813) was born in 1775, and during her lifetime there were hair-raisingly huge changes in fashion. If you visited Austen’s England during the 1770s you’d see ladies wearing absurdly high head-dresses. A triangular cushion or ‘system’ of horsehair three inches thick by nine inches diagonally, and seven inches in height, was fastened to a lady’s head with ‘black pins a quarter of a yard long’, as Maria Edgeworth explained in her novel Harrington (1817).

On top of this cushion: ‘the hair was erected, and crisped, and frizzed, and thickened with soft pomatum, and filled with powder…and made to look as like as possible to a fleece of powdered wool, which battened down on each side of the triangle to the face’. Next, ‘curls’ from the ear down to the neck were placed on each side of the ‘system’. Then ‘the hair behind, natural and false’ was ‘plastered together to a preposterous bulk with…powder and pomatum’ so it formed chignon.

Hester Lynch Piozzi (Mrs Thrale) in the 1780s. Note the high headdress and wig. An engraving by E. Finden after Sir Joshua Reynolds. Johnsoniana Vol. I, Henry G. Bohn, 1859.

Finally, the mound of hair was crowned with a ‘gauze platform’ from the centre of which ‘rose a plume of feathers full a yard high’; sometimes a jaunty ‘fly-cap’ adorned with flowers was worn instead of the platform. Ladies bent forward when going through doorways, and when travelling by carriage, they sat on the floor so that they could fit inside the vehicle.

These head-dresses were worn for up to a month, so head-lice took up residence; a ‘scratch-back’ came in handy for relieving an itchy scalp. A scratch-back was a decorated stick carved from ivory or wood, about a foot (30.5 cm) long, with a curved ‘hand’ at one end.

Hairstyles and fashions for October 1798. Austen played on the pianoforte every day when at home. Lady’s Monthly Museum Vol. 1, (Verner & Hood, 1798).

During the 1770s and 1780s, a wig powdered with starch such as flour was de rigueur for gentlemen; liveried servants and domestics wore wigs, too. Then the French Revolution came along. The writer Nathaniel William Wraxall pinpointed the ‘Era of Jacobinism and of Equality in 1793 and 1794’ as the death-knell of formal dress and wigs for everyday wear. ‘Cropped hair… together with the dis-use of hair-powder, characterised the men’. Ladies cut off their long tresses, too, ‘“a la Victime et a la Guillotine”, as if ready for the stroke of the axe’.

A scarcity of grain led to William Pitt’s powder tax of 1795 (because flour was used for powder). The wig’s long reign ended. The Whigs quickly abandoned theirs to mark their opposition to Pitt’s Tories, now dubbed ‘guinea-pigs’ (because the tax was a guinea per head).

Wigs did not disappear altogether; men still wore them to cover bald patches, and the royal family, clergymen below a certain income (like Jane Austen’s father George), and lower ranks of the army and navy were exempt from the tax.

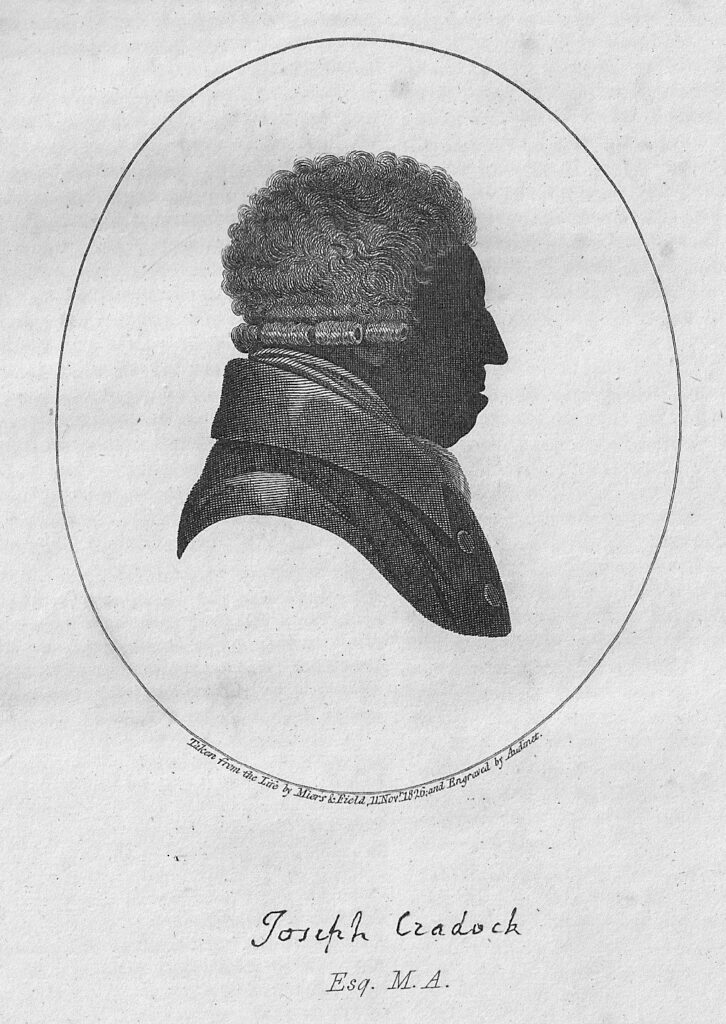

Portrait of Joseph Cradock (1741–1826), showing the type of wig formerly worn by all gentlemen before the advent of ‘cropped’ hair. Gentleman’s Magazine, 1827.

The Hon. Amelia Murray recalled that women not in the first flush of youth ‘very generally wore wigs’ even after the turn of the nineteenth century. ‘The Princesses had their heads shaved, and wore wigs ready dressed and decorated for the evening…Widows almost always shaved their heads; my mother’s beautiful hair had been cut off for her deep mourning, and she never wore anything but a wig in after years’.

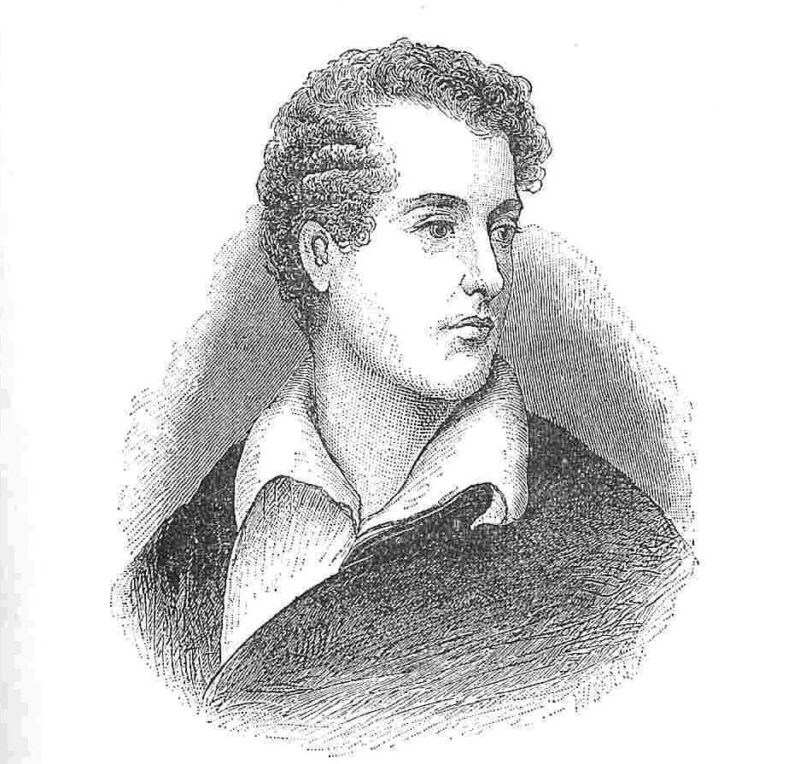

So if you visited England at the turn of the 19th century, you’d see young people wearing their own hair ‘cropped’ and un-powdered: wigs were now ‘old hat’. The poet Lord Byron and Jane Austen’s brother Charles wore short hair despite its republican connotations.

The poet Lord Byron – sporting the famous ‘Byronic crop’. Great Authors of English Literature, W. Scott Dalgleish, (Thomas Nelson and Sons, 1899).

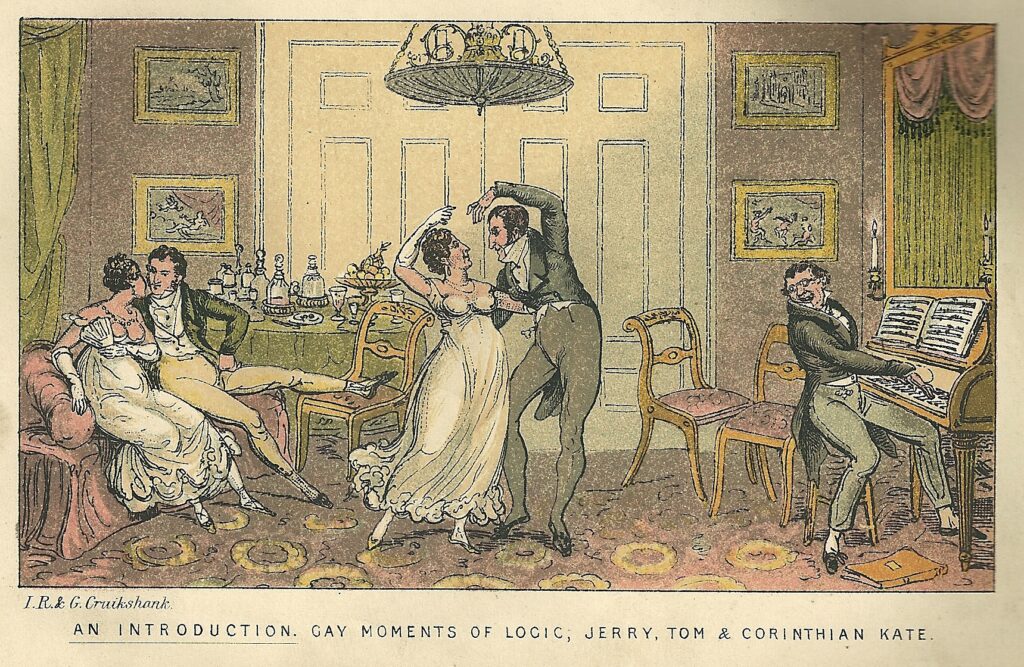

Young ladies wore short hairstyles, too; a few curls or ringlets artlessly framed the face. Curling-papers were used for styling – a maidservant helped with this task. In Austen’s Emma: ‘The hair was curled, and the maid sent away, and Emma [Woodhouse] sat down to think and be miserable’.

For ‘full dress’, ladies wrapped a velvet or silk bandeau or filet around their hair. A silk head-dress or turban adorned with jewels, or fluffy white ostrich feathers was very fashionable, too. When Catherine Morland attended her first ball at Bath in Austen’s Northanger Abbey, the ball-room was so crowded that she saw little of the dancers except ‘the high feathers of some of the ladies’.

‘An Introduction’. Corinthian Tom dances with his mistress Kate, Jerry chats to Sue, and Bob Logic plays some music. None of the young gentlemen or ‘ladies’ are wearing wigs. George and Robert Cruikshank, Life in London, (John Camden Hotten, Piccadilly, 1869).

Caps were worn for ‘undress’ at home, and for evening wear. On 1 December 1798, Jane Austen wrote to her sister Cassandra: ‘I have made myself two or three caps to wear… and they save me a world of torment as to hair-dressing, which at present gives me no trouble beyond washing and brushing, for my long hair is always plaited up out of sight, and my short hair curls well enough to want no papering’. Jane clearly found hairdressing tiresome.