Best known for her classic crime novels, one of Agatha Christie’s greatest mysteries was not a work of fiction but was rather a real-life enigma which cast Christie herself as the leading lady. On Friday 3rd December 1926, just after 9:30pm, Christie checked to see if her seven-year-old daughter Rosalind was sleeping soundly before making her way outside, getting into her Morris Cowley and driving away. Christie would be missing for the next eleven days but what exactly happened during this time is enshrouded in mystery and speculation and no one can be certain as to what one of Britain’s greatest novelists did during this time.

Christie’s disappearance was a great cause for concern and the authorities sparked a massive man-hunt to locate her. One thousand policemen, hundreds of civilians, and even Christie’s fellow crime writers, Sir Arthur Conan Doyle and Dorothy L. Sayers were drafted in to aid the search. William Joynson-Hicks, Home Secretary at the time, pressed the police force to find Christie quickly, hoping that the supposed expertise of Conan Doyle and Sayers would significantly impact the progression of the case. It was clear that Christie was to be found quickly and, for the first time, aeroplanes were used in the attempt to solve the mystery of her disappearance.

The tabloids too were quick to pick up the story and it wasn’t long before they were creating speculation, presenting ‘solutions’ to the mystery. This was perfect fodder for the hungry press; a real life disappearance with more than a few elements of Christie’s novels intertwined.

Shortly after the search commenced, Christie’s car was located at Newlands Corner near Guildford but this discovery did little to solve the mystery. The car was abandoned, the only trace of Christie being a fur coat which she had left behind along with her driving license, strewn across the seats. Christie was nowhere to be found and there was no obvious evidence that she had been involved in an accident.

Quick to turn the discovery into a juicy story, the tabloids began speculating that Christie had committed suicide. A natural spring known as the Silent Pool was located close to Christie’s abandoned Morris Cowley and two young children had reportedly died there previously. Some journalists, therefore, made the assumption that Christie had become the Pool’s third victim. But there was a major flaw with this theory- no body could be found. The theories were quick to be dismissed, after all Christie’s career was at an all-time high (her sixth novel, The Murder of Roger Ackroyd had recently been published and was selling well), what reason could she possibly have had for wanting to commit suicide?

In fact, behind the veil of her literary success, Christie’s personal life was far from successful and marital problems had cast a large shadow over the writer’s life. Her husband, Archie Christie, was a serial cheat and was known to have a mistress. Prior to Christie’s disappearance, Christie’s husband of twelve years had declared that he wanted a divorce, having fallen in love with a woman named Nancy Neele and it is not impossible that the combination of this shock declaration and the death of her mother earlier that same year cause Christie to become depressed. Could she have fled out of desperation? Nothing could be concluded until she was located.

Eventually, after eleven days of intensive searching, Christie was found 230 miles away in Harrogate, Yorkshire. Using the surname of her husband’s mistress, she had taken a room at the Swan Hydropathic Hotel, telling her fellow guests that she had recently travelled from South Africa following the loss of her baby daughter. Clearly, whatever had happened to the novelist, her creativity remained undamaged. At the hotel, Christie was seen playing the piano, singing and dancing yet she remained unrecognised, despite the fact that her image had been prominent in the media, even making the front cover of the New York Times.

Though Christie seemed to be physically well, however, her actions whilst in Harrogate suggest that she may have suffered mentally. As the medium employed by Conan Doyle in the search proclaimed “[she] is half dazed and half purposeful”. Prior to her discovery, she had placed an advertisement in The Times which said: “Friends and relatives of Teresa Neele, late of South Africa, please communicate. Write Box R 702, The Times, EC4”. Why would Christie issue such an advertisement knowing full well that she was not Teresa Neele? Could it be that she genuinely believed she was the grieving South African mother?

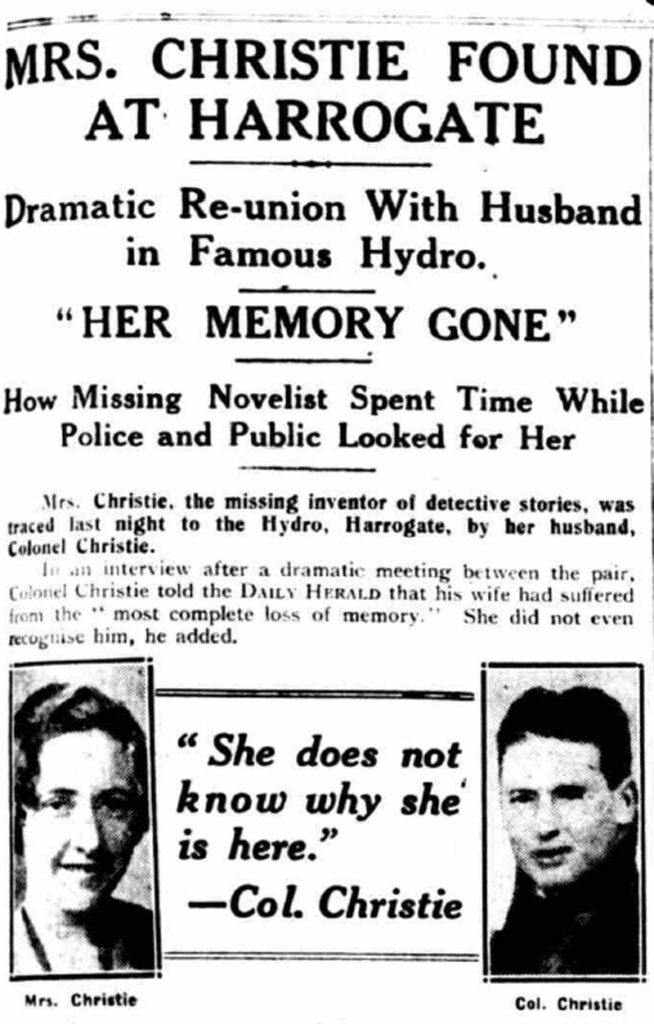

When Christie was found, she claimed to have amnesia, having no recollection of her journey to Harrogate. Her husband was sent to identify her and he later claimed “she does not know me and she does not know where she is”, Christie having introduced him to a fellow guest as her brother. A number of psychiatrists attested to the fact that Christie had suffered amnesia and this theory has always been maintained by the Christie family.

However, I have my doubts about this theory. Some at the time shared my doubts, offering theories which ranged from her staging the event to increase her profile (her book sales did increase as a result of her disappearance) to her staging the event to humiliate her cheating husband and enact her revenge. Most recently, it has been claimed by Andrew Wilson in his novel about Christie’s disappearance, that Christie was suicidal but after a failed attempt was persuaded by her religious convictions that her actions had been sinful and so she constructed the story to protect herself from shame.

Christie’s interview in 1928 seems to confirm the theory that she was depressed as she detailed having seen a quarry at Newlands Corner and feeling a desire to drive into it, only stopping herself because her daughter was in the car. Instead she fled that evening in “a state of high nervous strain with the intention of doing something desperate”. She let go of the wheel around Newlands Corner and struck something which jerked the car, hitting her head on the steering wheel. In her daze she caught the train to Waterloo, crossed to King’s Cross then caught another train to Harrogate.

However, to me, it seems unlikely that an individual who had been dazed from a car accident would be lucid enough to take not one but two trains. In my opinion, Christie had planned every detail of her disappearance, intending all along to plant her car, travel first to London and then Harrogate and then eventually be discovered, living under the name of her husband’s mistress. It is my belief that having been asked for a divorce, Christie set out to facilitate this with as little shame to herself as possible. If she can be seen as zealous enough to condemn her own suicidal thoughts then it is plausible that she was pious enough to view divorce negatively. By living under the name of her husband’s mistress, she brought to the attention of the press her husband’s affair, removing blame from herself and attributing it to her husband’s infidelity. This is further confirmed by Christie’s unwillingness to hide away in Harrogate. Her public activities suggest that she want to be found and that she wanted to divorce her husband without shame. Her creation of her amnesia was the final piece of yet another fictitious masterpiece. Not only would this have further facilitated her divorce but it would also have prevented the press from prying into her personal life- by claiming she could not remember the reason for her disappearance, her husband’s infidelity, she prevented the press from both asking her difficult questions and creating salacious gossip.

Thus, Christie’s disappearance was, in my opinion, one of her greatest masterpieces, allowing her to maintain grace and decorum in the face of a humiliating divorce case. Her husband did go on to marry Nancy Neele and Christie secured herself a place in history as one of Britain’s greatest novelists.